【 REPORT – 3 】Smart Illumination Summit 2019 Panel Discussion

TYPE: TALK

CATEGORY: Smart Illumination Summit

Smart Illumination Summit 2019 invited guest speakers from creative cities around the world to search for the next steps in the Smart Illumination project.

The second part of the summit featured presentations by Smart Illumination Yokohama’s art director, Tsutomu Okada, and Masato Nobutoki, the chair of the Executive Committee, followed by a panel discussion led by Smart Illumination Yokohama’s chief planner, Shinichiro Moriya.

日本語はこちら

■Theme

"How can art interact with cities -Strategy of a creative city in the age of the SGDs"

■Program

【Part2|panel discussion (3 cities)】

Speaker :

・Ignatius Hermawan Tanzil / Founder and Creative Director LeBoye design and Dia.Lo.Gue artspace

・Chisato Shimada / Urban Planning & GIS expert /New York City, USA

・Tsutomu Okada / Art Director, Smart Illumination Yokohama

・Masato Nobutoki / Chairman, Smart Illumination Yokohama Executive Committee

Facilitator :

・Shinichiro Moriya / Chief Planner, Smart Illumination Yokohama

*Lyon City, France was scheduled to attend but cancelled due to their circumstances.

Tsutomu Okada: First, I would like to highlight this table around which we are all seated. It was created by Rintaro Hara. The original plan for this summit was that representatives from four cities would take part, so it should say “Jakarta,” “New York,” “Yokohama,” and “Lyon” around the table, though sadly our guest from Lyon was unable to come in the end. There was also a suggestion from someone that the four of us could play table tennis later [laughs]. Mr. Hara, please share with us about your work.

Rintaro Hara: I made two table tennis tables. One makes a noise like a xylophone, the sounds changing from high to low depending on where the ball bounces. The other table was made especially for the summit with maps of the four cities.

Shinichiro Moriya: At today’s summit, instead of table tennis, I hope we can enjoy a verbal rally of ideas between the guests. I would like now to ask Mr. Okada, who is the art director of Smart Illumination Yokohama, to introduce that event for us.

Okada: When we said “development” in the past, it meant reclaiming land, building bridges, constructing buildings, and so on. You needed a lot of money and power to do it. But as society has matured, so to speak, the budget for public expenditure has decreased and instead we see the need rise for doing something more creative. We piggybacked on this and pondered how we can apply art to actual society, so we initially researched case studies from around the world of cities changing through spectacle-like artistic expression.

Yokohama night view project・Miyakobashi

The following year, we took a searchlight and camera, and went on a walk around the city of Yokohama. Here you can see what things looked like at the time. This is Miyakobashi, a unique and famous place in Yokohama where there are rows of small bars. Along with Kyota Takahashi, an artist who is also taking part in this year’s Smart Illumination, we put up light decorations, shone the searchlight on it, and then took photos by photographer Hideo Mori.

Yokohama night view project・Mitsui-soko

Another example is an old warehouse that a company called Mitsui-Soko owns. It’s not a sightseeing spot and lies outside the port area, so basically no one knew about this lovely building. We shone light onto it to bring attention to this scenery. We realized the benefits of applying artists’ perspectives and light in this way, and became determined to launch a festival from 2011 that focused on light.

But as you know, then the Great East Japan Earthquake hit on March 11, 2011, and suddenly we were plunged into a state whereby we could no longer trust our convenient lives until then. I imagine this was the same for New York in 2001, but we had many long discussions with city officials where the idea of doing a light festival at such a time sounded ridiculous. But then we reached a consensus that it was at precisely this kind of time that we should all come together to do something and we decided to hold a festival of light.

But we deliberately didn’t want it to be one of those events you often see recently in Japan, where it’s like a competition to see how many light bulbs you can put up and create lots of glittering lights. Since we wanted it to be an illuminations event that feels meaningful for the times, we added the word “smart” to the title. This incorporates various meanings, but, in brief, the project started with the intention of creating a new kind of night view by pairing environmental technology and energy-saving technology with the creativity of art, or of creating a place for talking about energy and future lifestyles. This is why we don’t do things like the projection mapping that is so trendy these days. Yokohama’s scenery at night is blessed with a waterfront and is very attractive, but we wanted to see how its appearance might be transformed by bringing in artists.

Smart Illumination Yokohama 2011

《WRAPPING THE CITY LIGHTS》Kyota Takahashi

In this case, we just added color filter to the existing lights but it made the scenery into something fresh and exciting for people who normally visit the area.

Smart Illumination Yokohama 2011

《SHINING SMILE FRUIT》Kyota Takahashi

This is a project by Kyota Takahashi called Shining Smile Fruit in which children draw pictures on bags that are used to grow fruit. For the first year, around 3,000 of these that were drawn by children from Rikuzentakata in Iwate Prefecture, which was hit hard by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, were placed in Yamashita Park. As a park whose land was originally reclaimed using rubble from the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, we consciously linked its historical context with the situation in Rikuzentakata.

Smart Illumination Yokohama 2014

《CHIBIHI Project》Toru Koyamada

I just said that Smart Illumination Yokohama is an event for talking about things and, in fact, we have even held bonfires to inspire people to think about the primitive nature of light. This was a project by Toru Koyamada, one of the central members of the media art collective Dumb Type. We lit several bonfires in Zou-no-hana Park and then visitors sat around them talking with the artist. For some reason, people felt more able to open up when gathered around a small fire, and shared unthinkable stories or talked about their dreams. This was an extremely good strategy.

One of the things we take pride in about Smart Illumination is that the event is the darkest illuminations in the world. In the future, when viewing the Japanese archipelago from a satellite up in space, I want to see what it looks like with just Yokohama in complete darkness.

Moriya: I would now like to move things onto the presentation from Masato Nobutoki, the chair of the Executive Committee. Originally the head of the Yokohama municipal department in charge of measures to combat global warming, he joined the Smart Illumination team from the perspective of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) and the environment. I would like to ask him to tell us about what he found significant about this project.

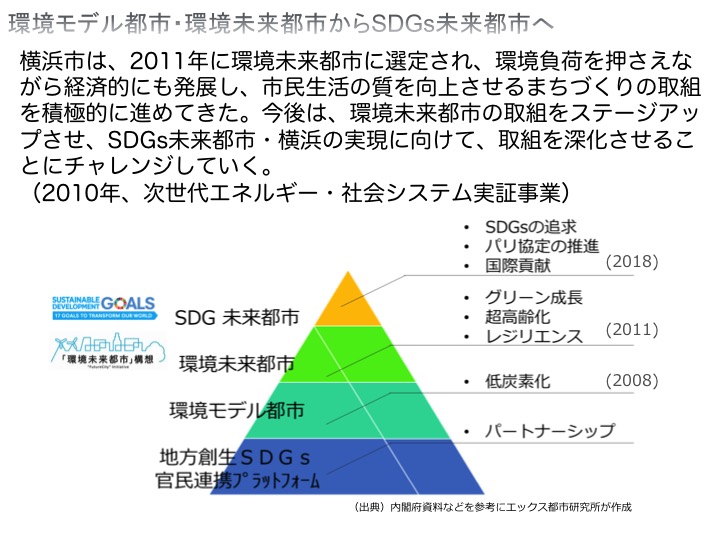

Masato Nobutoki: In 2008, Japan set a goal of becoming a low-carbon society. Yokohama was designated an Eco-Model City and, accordingly, to demonstrate next-generation energy systems for society for the 2010s, it began installing smart grids around the city. In 2011, the FutureCity Initiative was launched. At the time, these were determined in order to engage with the two major social issues for international cities of global warming and the aging society.

And then in 2018, Yokohama was designated a SDGs FutureCity and was fortunate to become a model for initiatives. In this way, the city has been designated in four ways in a pyramid structure, sharing this status with only Kitakyushu City. In 2011, the year that Smart Illumination Yokohama started, the FutureCity Initiative also began.

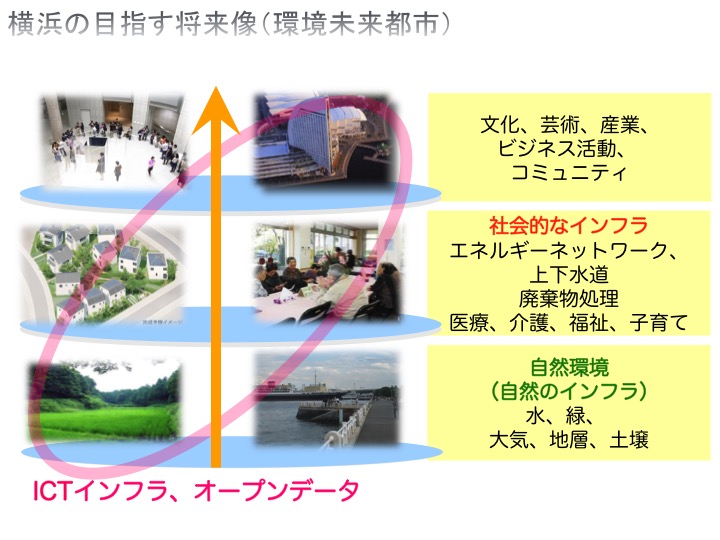

This is a diagram that I made in an attempt to think of the city as three layers. Art and culture are at the very top. Below it, as written in red, is social infrastructure, meaning things like energy, the water supply, waste disposal, and healthcare and other “soft” types of infrastructure. Below that is what has started to attract attention of late: natural infrastructure. It means people are starting to look again at water, greenery, the air, and geological strata. The orange arrow is information and communications technology. It relates to all the layers. The pink ellipse shows the city’s policy whereby we should run the city with the mindset of open data.

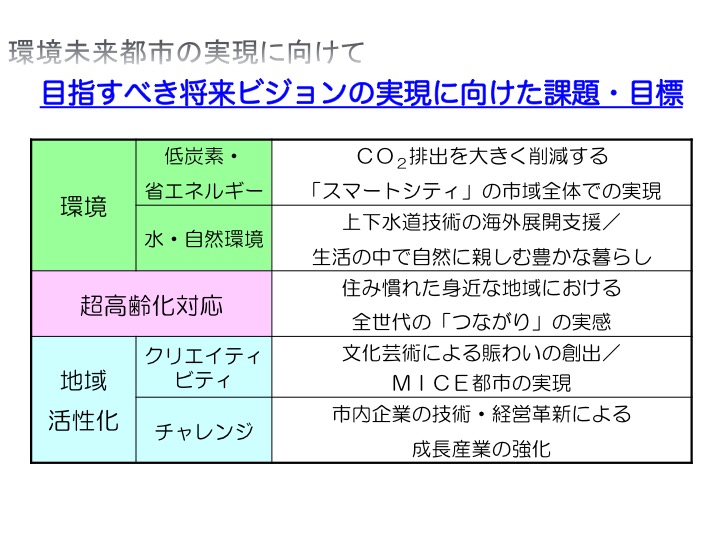

In order to realize this, we made five pillars as a FutureCity. All cities must tackle the chronic issues of global warming, the aging society, and declining birth rates, though a city then selects its respective targets and issues according to its own context. The bottom two are particularly related to culture and the arts, though at the time, only Yokohama was alone in including these. Yokohama wanted to raised its profile as a creative city.

When I announced this, one of the members of the committee remarked that having five areas like this was fine, but unless you connect them horizontally, it will end up like a vertical hierarchy. “Do you have a project like that?” I was asked. And I could tell them that I had a representative one with Smart Illumination Yokohama. It is covering all five issues.

After Yokohama became a SDGs FutureCity, Yokohama City formed the Yokohama SDGs Design Center with various partners (Kanagawa Shimbun, Toppan Printing, EX Research Institute, Television Kanagawa, and tvk Communications). I serve as the head of the center. In order to create new social design with the SDGs for the needs and seeds of corporations, universities, citizens, and other stakeholders, it undertakes marketing, coordination, planning, and innovation, and aims to achieve the ultimate goals.

A lot of people are talking about the SDGs now as something fun and exciting, and it is indeed the first example of international communication design of its kind in quite a while, but people don’t talk about the Paris Agreement. Because it involves the total reduction of carbon emissions, the Paris Agreement usually just discarded as too difficult to achieve. But our future world actually needs both of these initiatives. My generation spent years using lots of electricity and pumping out carbon dioxide, but in the age where we will endeavor not to use energy or, if we do, to use renewable energy, the SDGs are attempting to raise and maintain our quality of life, so we are actually aspiring toward something we have never experienced before. We must think about what is possible for us to do while keeping this in mind.

From an Eco-Model City to the Yokohama Smart City Project and the FutureCity, Yokohama has undergone various kinds of “warm-up exercises.” But now as an SDGs FutureCity model, we have arrived at a time when we must go from an era when mass productions, consumption, and waste symbolized affluence to an era that seeks the new kind of affluence befitting the 21st century. When thinking again about the value of Smart Illumination Yokohama in this context, we can take three approaches: the approach that tackles the three issues of the environment, economics, and society; the approach that aspires toward new affluence while aiming for carbon neutrality; and the approach that, naturally, includes the city’s history until now as a creative city. Yokohama’s new technology should be presented first not at trade fairs and exhibitions but through art. Smart Illumination Yokohama is an event that symbolizes such an approach. And then this will lead to fun, rest, communication, creating new technology, human resources training, value improvement for the whole city, and a move away from our models of consumption. Those who went around the exhibits will have understood this, but it’s not simply about enjoying the experience of watching something, but about communicating with the creators.

In terms of the 17 goals of the SDGs, everyone will probably have different ideas about where an event fits into them, but it’s not the case that doing everything will automatically take us to the next step. All government bodies are now involved with various initiatives and what is vital is how this becomes a narrative. With Smart Illumination Yokohama, it starts with the ninth SDG of industry and technological innovation, but expands and deepens to encompass the issue of energy and then gender.

【DISCUSSION】

Okada: I have so many things I want to ask Ms. Shimada. First, why are you working as a city official in New York City?

Chisato Shimada: I became interested in the environment and nature because I grew up in Kyoto. At first, I studied forestry and environmental science in traditional way, but then I realized that what I liked was the green/natural environment where I am surrounded by in my daily life rather than the scientific side of it. That led me to pursue the career in city planning and community development. Rather than leaving Kyoto for somewhere like Osaka that was basically still the same, I decided to take the plunge and leave Japan and go to a big city, which was how I came to New York City.

Having lived abroad for a long time, I have realized that I want to provide outside perspectives and support people who are working in Japan like yourself. By sharing information from outside Japan and exchanging the ideas, I hope that what I do in New York City can come prove useful in some way in Japan and, likewise, as a Japanese person living abroad, I hope that I can introduce the things I have learned from Japan to people overseas.

I think that, as the society changes in the future, how I view/think would change accordingly. But I want to continue doing what I have been doing while enjoying it.

Okada: What do you like about New York City?

Shimada: Is this in terms of the physical spaces or the social aspects, or both? The good thing about being in New York City is that I am no longer afraid to fail. In New York City, I have experienced all kinds of challenges and have learned a lot from the mistakes I have made, but society accepts who I am. Therefore, we can try various different things, Even someone like me who is a foreigner, can find a way to work for the city government. In this sense, anything is possible as long as you try hard enough. That is what New York City makes special.

I think it is wonderful what Tanzil said in his presentation about expanding art scene with the help of the private sector. If we compare this with places like New York City where that kind of culture already exists, the way of starting is different.

New Yorkers use public spaces as if they are their own backyards, so it’s hardly like going somewhere special. It is like there is an embedded sense of ownership to those spaces. that’s why communities often spontaneously participates in the parks management. I feel that this is a cultural difference.

In Jakarta, how do people feel about public spaces? How are people in the city consious of such spaces?

Ignatius Hermawan Tanzil: As I mentioned before, there is not so much public space in Jakarta. There are not so many parks or places where we can go. I believe that education and experience about this is really lacking. Of course, I am sure the young generation is now changing. Before, luxury meant going to Singapore, Hong Kong, or Japan to buy high-brand clothing, but young people today rather want to visit the lesser-known places in another country or go to some village where there is a lot of nature. Social media can be harmful but as one example of its positive impact, we can see that the younger generation is now seeking out this kind of thing.

My friend and I always dreaming of changing our Bintaro into a place like Copenhagen, where the whole city is so beautiful. Every shop is so beautiful. Design thinking is already in their blood, it’s part of everything. Good design does not have to be expensive. And this is why we are doing just these small things but hopefully someday, the government will pay attention and help us out.

Moriya: Tanzil just mentioned education. I was wondering what Committee Chief Nobutoki thinks about this point, particularly in relation to the value of public space or the value of design and art.

Nobutoki: Just from a look at the number of nonprofits there are, it seems like a lot of people in Yokohama are thinking about public space or ways to tackle global warming.

Right now, I am involved with a project related to the sea, which is also a kind of public space. But members of the public are actually only able to enter 1.4 kilometers of the 140 kilometers of sea along the coastline of Yokohama—a mere one hundredth. Moreover, these areas are embankments or reclaimed land that are designated harbors or fishing zones. So public areas or zones equates to somewhere that is managed. In foreign countries, a harbor area is a place where you can swim. But what’s happening in Yokohama is that people are unable to swim in the sea that is right there in front of them or have never experienced catching something to eat in that water. Such is the case almost everywhere in Japan and I would somehow like to reinvigorate this state of affairs.

Moriya: Art is able to do things that are not normally possible. Take the example of the bonfires that Okada introduced in his presentation. Ordinarily, we could never do that. Art is also something ultimately based on the personal interests and concerns of the artist, but I would like to hear from Director Okada about art’s forte.

Okada: In Yokohama, deregulation of public space is well underway. I think this stems from a desire, in the face of stagnating tax revenues and since we have public space all around us, to utilize this resource, so to speak, and employ it as a tool that can make money. In the same way, we can also valorize public space in terms of the common assets that art and creativity possess, so by pairing these things with public space, I think it’s possible to turn them into profit. Smart Illumination Yokohama is one such experiment but we are also engaging in this in various other projects on a daily basis.

Text: Mana Saito

Photos: Ayami Kawashima